About the Journey

What inspired you to become a wildlife photographer, and how did your journey begin?

As a child, I dreamed of keeping a horse in our small apartment. I think it was clear to my parents back then that this idiot was going to grow up a little differently. The herd mentality took over during my college years, though, and I became an engineer, eventually completing my master’s in computer systems from a quaint place called Troy in upstate New York. It was there, amidst the serene hills, that I felt a magical pull back toward nature.

My first purchase as a Teaching Assistant in the US was a Nikon SLR, and that was the beginning of it all. Once I returned to India, I decided to explore some of the country’s national parks. Pure luck led me to start with Ranthambhore, where I had the fortune of meeting Aditya “Dicky” Singh. That trip marked the start of what has now been 20 years of absolute madness—and counting.

Can you share the story behind one of your most iconic photographs?

Iconic is a heavy term, and while I don’t believe any of my images have reached that level just yet, the image of the Southern White Rhino has undoubtedly brought me my biggest recognition so far. When I first arrived at Solio Game Reserve, I was unprepared for what to expect, especially the type of forest it harboured. Upon arrival, I was immediately captivated by the landscape—rolling hills, lush yellow-fever forests, winding rivers, and reeds that created an awe-inspiring habitat. Solio is renowned for its massive rhinos, and it stands as one of the greatest success stories of conservation, demonstrating what humans can achieve when we pour our hearts into a cause. Each morning, I was drawn to the forest cover, particularly during the early hours when light would gently filter through the striking yellow-fever trees. It became a daily dream to encounter a rhino as I ventured through the forest to reach their foraging grounds. Then, one day, I was blessed with the perfect conditions: a stunning rhino, bathed in beautiful backlight, right in front of me. This image speaks volumes to me—it reflects the resilience, strength, and vulnerability of the species. Rhinos, though incredibly strong, have a trusting nature, and therein lies their vulnerability. Winning the HIPA 2024 award for this image is not only a great honour, but it also fuels my hope that it can contribute, even in some small way, to the fight against rhino poaching.

How has winning multiple international awards shaped your career and perspective as a wildlife photographer?

Honestly, it took me some time to comprehend this question. I am an out and out introvert as a person and global recognition is scary sometimes for me. Having said that, I distinctly remember feeling ‘validated’ when I first won an award. I guess at some level every artist seeks validation of some sort. How extrinsic or intrinsic that need is will differ from person to person. To come back to your question, I guess once that first award came my way (by sheer luck) it gave me the confidence that I am probably not doing anything too wrong. I won’t say it gave a direction to my photography, but I felt happy that my kind of photography is being liked by folks. It gives me hope that as time progresses more and more wildlife photographers will tap into their creative side, and I am sure that will lead to some beautiful art.

The second part of your question which relates to ‘career’ part of it, I think winning awards has given me as a wildlife photographer the necessary exposure and reach for my workshops. Winning multiple awards at the very least will give a potential guest the confidence that this chap knows about wildlife photography. Whether I then turn out to be able to impart that knowledge and eye to the guests is a different matter.

Creative Process and Techniques

What’s your approach to capturing the perfect wildlife moment?

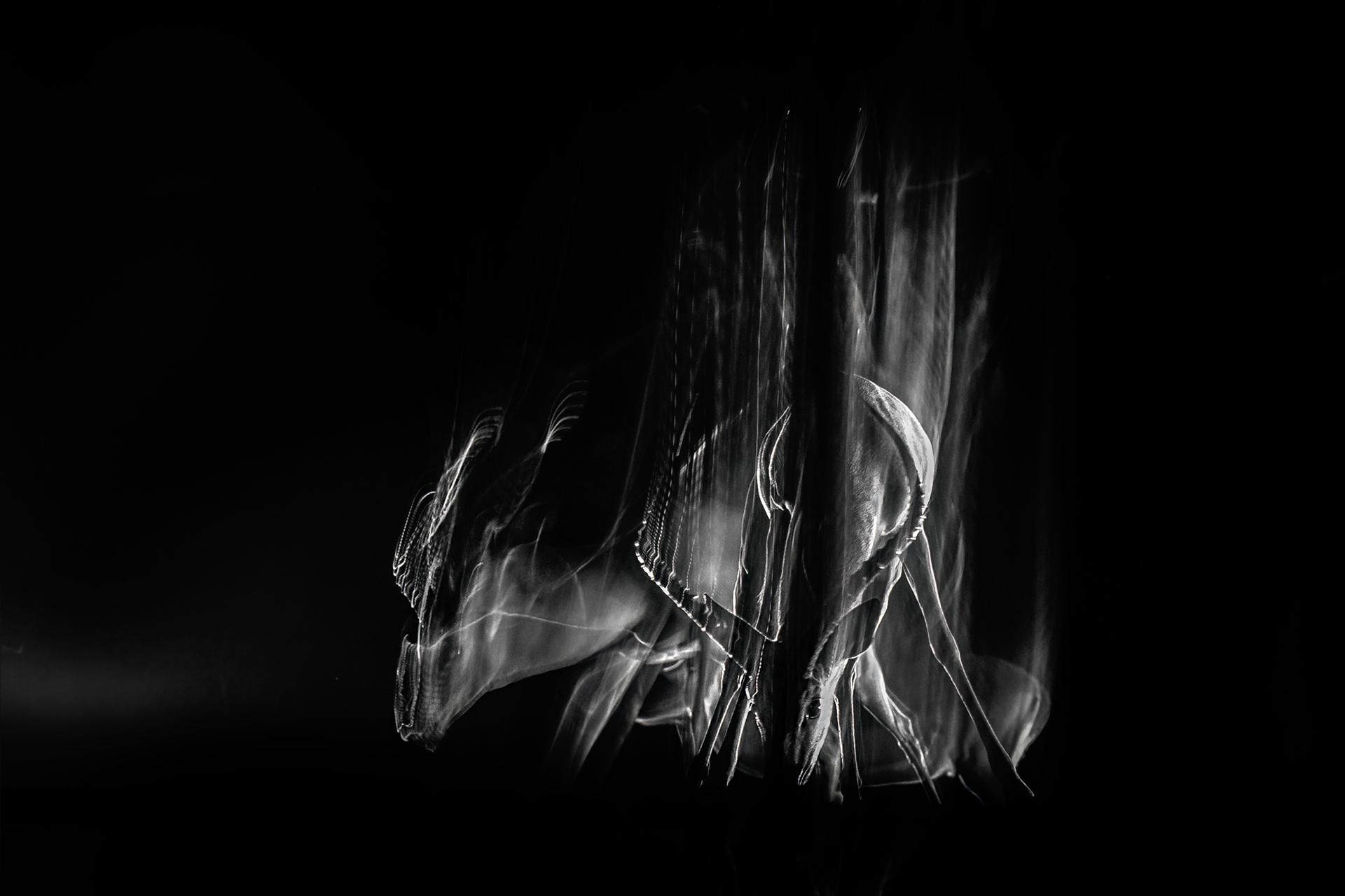

Capturing the “perfect wildlife moment” is, for me, about visualizing how light interacts with the scene. I focus on the interplay of light and shadow, waiting for the perfect alignment that elevates the mood and composition. Wildlife is unpredictable, but light is a constant guide—I prepare, observe, and hope to capture a fleeting moment when the light transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary. It’s about creating images that evoke emotions. Perfect wildlife moment in that sense for me is about great interplay between the elements in the frame and not just about the perfect natural history moment.

How do you prepare for a wildlife photography expedition?

If I could ask one question to all the photographers I admire (and there are many), it would be this. Preparation, I believe, is everything—it is not just about what you pack but how you meticulously plan every detail of the expedition.

Here’s my approach:

• What do I want to photograph? (e.g., Big Tuskers)

• What kind of images do I want? (e.g., Dusty, backlit scenes)

• Where should I go? (e.g., Amboseli)

• Why is this location ideal? (e.g., Dusty conditions, a strong elephant population, and a trusted guide)

• When is the best time to visit? (e.g., Dry season to maximize dust)

• Where should I stay? (e.g., Inside the park to minimize travel time)

Once I have clear answers to these questions and feel confident about them, I know I’m ready for the journey ahead. It’s this process that equips me with the foundation to make meaningful images on the expedition.

Can you describe your post-processing workflow and how you maintain authenticity in your images?

In the age of AI, this is such an important question. I wish I could give you a precise 10-step workflow, but my truth is different. Most of my post processing begins in the field—when I’m photographing, I already visualize the final image. This vision shapes my workflow when I return to the computer.

I primarily use Adobe Camera Raw for processing. My starting points are usually the Whites, Highlights, Shadows, and Blacks controls—I adjust these almost instinctively. The Dehaze tool is another favourite, particularly for enhancing skies. Since I work extensively in black and white, I dedicate time to manual conversions, tweaking the primary colours individually to create the desired tones and depth.

Beyond these basics, I keep things minimal. I dislike cloning and prefer to focus on refining the image as close to the original scene as possible. I absolutely despise the use of blurring and the addition of directional light in processing. Something that seems to have become the norm these days.

By sticking to these principles, I ensure my images remain authentic and true to the moment I experienced in the field.

What gear do you typically use, and how do you adapt to challenging conditions in the wild?

My gear is carefully selected for versatility and optimal performance in various environments. I primarily use Canon cameras, such as the Canon EOS R5/R3, and more recently the R5 Mk2. My go-to lens for most situations is the Canon RF 100-500mm f/4.5-7.1 L IS USM, offering both flexibility and exceptional image quality. For wildlife in challenging conditions—particularly extremely low light or when the potential for creative bokeh is high—I rely on the Canon 400mm f/2.8 lens. Since I often do vehicle-based game drives, a couple of bean bags are always on my packing list to stabilize the gear.

Regarding challenging conditions like dust, rain, snow, or heat, I’m fortunate that most of my gear is highly weather-sealed. I always keep protective covers handy, designed specifically for field use, to shield my gear from the elements. However, I’ll admit that in the event of a dust storm or heavy rain, if I don’t have the rain covers for my camera and lens, you’ll still find me shooting without hesitation. The only rule I follow in these situations is to ensure I clean the gear thoroughly as soon as I get back to camp.

Challenges and Lessons

What are some of the most significant challenges you’ve faced while photographing wildlife?

Predicting weather has become one of my most significant challenges in recent years. My photography trips are highly targeted, designed around specific natural phenomena—such as polar bears on sea ice, elephants in dusty conditions, or the elegant, red-crowned cranes dancing in the snow. Each of these experiences is heavily reliant on weather conditions, and the unpredictability of weather has been a constant obstacle.

I recall one particular year when I planned a trip to the Masai Mara during what was historically to be one of the rainiest months. My goal was to photograph animals in the rain, capturing the dramatic interplay of wildlife and weather. Despite spending nine days in the Mara, there were only 30 minutes of rain during the entire trip. Experiences like these highlight the growing unpredictability of weather, which I believe is increasingly influenced by human impact on the environment.

So yes, I can confidently say that weather—and its indirect connection to human activity—has been one of my toughest challenges to navigate.

Have you had any dangerous encounters in the wild? How did you handle them?

While wildlife is inherently unpredictable—a convenient term acknowledging our limited understanding—it is often human actions that precipitate dangerous encounters. I recall a particular zodiac excursion in a Svalbard fjord where we observed a male polar bear attempting to hunt a harp seal near a glacier wall. The bear was unsuccessful and continued its search for food. From our vantage point, we noticed its path was leading directly toward a group of tourists who had landed near the glacier.

We tried shouting to warn them, but our voices couldn’t reach that far. Acting swiftly, we navigated our zodiacs toward the shore to alert their guide, as they likely hadn’t noticed the bear approaching. Fortunately, we reached them just in time, and they retreated to the safety of their cabin in the fjord. The most concerning aspect of such encounters is that, had we not intervened promptly, the situation could have ended tragically for the bear. The guide might have been compelled to kill the bear to protect the tourists.

Incidents like these sometimes make me question if we should even be allowed near wildlife as our lives always seem to take precedence in times of conflict. It is a difficult question for me, one that I am not completely sure I want to think about.

What lessons have you learned about patience and persistence from photographing wildlife?

I’m so glad you used the term persistence—I truly believe that is where the essence lies. The drive to keep improving, to push harder, stems more from persistence and perseverance than from patience. Patience, for me, feels more innate, especially when I’m out in the wild, immersed in the natural world.

Over the past two decades of being deeply engrossed in wildlife photography, I’ve come to realize just how crucial persistence is in building meaningful connections. In my case, it is the bond I have formed with nature—a connection that deepens with every challenge and triumph. But the lesson extends beyond the wild; it is equally relevant to relationships in the human world. Persistence fosters understanding, trust, and depth in any bond, and that is a truth I hold close.

Conservation and Impact

How do you think wildlife photography can contribute to conservation efforts?

Wildlife photography is a powerful tool for conservation. It has the power to evoke emotions, create awareness, and inspire action. A compelling image can transport viewers into the heart of a wild habitat, showcasing both its beauty and fragility. For me, it is about telling stories—stories of resilience, vulnerability, and the interconnectedness of life. For example, my award-winning photograph of a southern white rhino at Solio Game Reserve was not just about capturing an image but about shedding light on the ongoing battle against rhino poaching. Such images can serve as a bridge, connecting people to nature and motivating them to support conservation initiatives.

Have you worked on any specific projects or initiatives aimed at wildlife preservation?

While I haven’t spearheaded large-scale conservation projects, I’ve contributed in ways that align with my photography. One example is donating prints to initiatives like Prints for Wildlife and the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, which use art to raise funds for local communities and wilderness preservation efforts.

These collaborations have been incredibly rewarding because they allow my work to directly support causes that matter deeply to me. It is a small but meaningful way to give back, helping to protect the habitats and wildlife I love to photograph while also uplifting the communities that live alongside them.

How do you balance the ethical considerations of photographing animals in their natural habitats?

I believe that with love comes care, and I hope this holds true for wildlife photographers. Most of us, I like to think, are deeply in love with the subjects we photograph. With that love, and the right knowledge, I trust that no one would intentionally harm wildlife for the sake of a photograph—though, of course, there are exceptions.

To foster this sense of responsibility, I place immense value on working with experienced local guides on all my trips. A knowledgeable guide doesn’t just help you find the perfect shot; they provide invaluable insights into the behaviour and needs of the wildlife and their environment. Over time, collaborating with such guides can profoundly shape your ethics and values, enriching your understanding of the natural world and deepening your respect for it.

Personal Insights

What role does storytelling play in your photography?

What story are we really talking about here—their story or mine? It is something I have reflected on deeply. Not all photographs are solely about the subject’s story; there’s always a piece of the photographer woven into them. For documentary photographers, the ability to dissociate from their own narrative is essential. But for me, I prefer to immerse myself in the story that unfolds within the photograph.

Every image I choose to process carries a story—a blend of the subject’s narrative and my emotional connection to it. It is never just about creating the prettiest picture; it is about crafting something that resonates on a deeper, emotional level. I connect with my images in a very personal way, and my hope is that they evoke similar emotions in those who view them. For me, a photograph isn’t complete unless it stirs something within the heart.

Is there a species or location that you dream of photographing but haven’t yet?

There are quite a few but I believe high on the list, very high would-be Penguins. In particular, the emperor penguins at Gould Bay, Antarctica. The environment they inhabit is nothing short of extraordinary—the vast, icy expanse, the relentless blowing winds that add an element of drama to every frame, and the magical light that paints the scene with an almost otherworldly glow. Ahh, it’s an absolute dream of mine to witness and photograph that.

How do you stay motivated and creative in such a competitive field?

I don’t think I consciously do anything to stay motivated—it simply flows from my love for what I do. Motivation feels effortless. My creativity, though, stems from a deeper desire: the urge to infuse a part of myself—my emotions, my perspective—into every frame. I’m constantly drawn to locations with dramatic light, tempestuous weather, and breathtaking landscapes, as these elements allow me to weave my thoughts and feelings into the image. Conducting workshops and tours in these incredible settings not only keeps my creativity alive but also inspires me through the fresh perspectives and interpretations of those I guide.

Ultimately, I remind myself that wildlife photography isn’t about competing with others—it is about building connections. It is about connecting with the subject, with the environment, and with oneself. By focusing on personal growth and my ever-evolving bond with the natural world, the creative spark not only stays alive but thrives

Advice and Future Goals

What advice would you give to aspiring wildlife photographers?

Focus on building a connection with nature before worrying about creating the perfect shot. Spend time observing, understanding animal behaviour, and learning about the environment you are in. Photography as an art form isn’t just about creating sharp and crisp images. Work on mastering your craft by experimenting with light, composition, and storytelling, and remember, it is not just about the technical aspects; it is about capturing the emotion and essence of the moment. Lastly, invest in the journey—travel to places that inspire you, collaborate with experienced guides, and don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Every misstep teaches you something valuable.

What are your future goals, both as a photographer and as a conservation advocate?

As a photographer, one of my primary goals is to champion wildlife photography as a legitimate and powerful form of art. I feel it is often underestimated, seen solely as documentation rather than a medium that can evoke deep emotions and tell profound stories. I want to push creative boundaries and inspire others to see wildlife photography as an art form capable of standing alongside any other.

On the conservation side, I aim to use my work to support meaningful initiatives, such as raising awareness about endangered species and fragile ecosystems That could be through collaboration with organizations to conduct workshops on their behalf or by simply donating prints. Expanding my workshops and tours is another goal—helping others connect with nature, embrace ethical practices, and see the artistic potential in their work. Ultimately, I want to leave a legacy that elevates wildlife photography and fosters a deeper, more conscious relationship between people and the wild.

Rahul Sachdev has been actively involved in wildlife photography since 2004 and has over the years built a strong portfolio which is recognized for its unique use of light and creativity. He has been conducting wildlife photography tours and workshops around the globe for over 12 years now, with the focus being to teach how...

By Ata Hassanzadeh Dastforoush | Photos by Ata Hassanzadeh Dastforoush

PT Explorers 5 Minutes read

ReadEmail: email@pawstrails.com